Recap: Midwest PHP 2017

"We have the most pointless and the most important jobs in the world. And Forgetting either is dangerous." - @eryno #mwphp17 #developers

— Dan Ficker (@deliriousguy) March 18, 2017

I recently attended and spoke at a conference in Minneapolis, giving my talk on basic UX for non-designers. It was my first time at Midwest PHP, and I had a great time (despite not being a PHP developer).

Here are my big takeaways, in no particular order.

Accessibility in web development is achievable, and we're not doing a great job

"Coders like challenges, right? Think of coding for accessibility as a technical challenge." - @vavroom #mwphp17

— Hilary Stohs-Krause (@hilarysk) March 17, 2017

At the speaker's dinner the night before the conference started, I met Nick Steenhout (and his unflappable service dog). Nick speaks and trains on web accessibility, and gave (for me) an eye-opening talk at Midwest PHP.

At Ten Forward, we've started down the path of more accessible web sites (for example, we use WebAIM's contrast checker, we work to give images alt tags, etc.), but generally, it's an afterthought. Part of that is underestimating how many users have accessibility needs - Nick says in the Western world, it's about 1 in 5 people - and part of it is ignorance as to the ways and means.

Easiest way to start building accessible tech: "A <button> is a button, a <div> is a div. Why change default behavior?" - @vavroom #mwphp17

— Hilary Stohs-Krause (@hilarysk) March 17, 2017Whoa! Didn't know WAI-ARIA was a thing. Learning a ton at @vavroom's talk on #accessibility and #development. #mwphp17 pic.twitter.com/de15Gjiyxo

— Hilary Stohs-Krause (@hilarysk) March 17, 2017

Key lessons learned: integrate WAI-ARIA, and make JavaScript listen for multiple types of interactions on an element (such as pairing onclick with onkeydown).

Learn more in this great article Nick wrote about why web accessibility is good for everyone.

Teaching is not just reciting what you know to someone who doesn't

"Humans are like computers - we have to have processing time," says @cattycreations. Longest adults can go w/out a break is 90 min. #mwphp17

— Hilary Stohs-Krause (@hilarysk) March 18, 2017

I knew this in a broad sense, having been raised by a teacher father, and from my experiences volunteering in coding education, but Heather White's talk on "learning to teach" provided new insight and multiple tools for being a more effective teacher.

Two parts that stuck out most:

1. The relationship between memory, and how we were taught what we're attempting to remember.

After 2 weeks, we tend to remember X of what we X:

— Hilary Stohs-Krause (@hilarysk) March 18, 2017

・10%, read

・20%, hear

・30%, see

・50%, see & hear

・70%, say

・90%, say & do#mwphp17

Essentially, to act upon is to cement to memory. I saw this firsthand just the other week, with the marked retention (and engagement) contrast between having 6th graders watch a powerpoint lesson on video embed code versus physically adding videos to their codepen sites.

2. Relatedly, there are clearly defined ways to teach and styles of learning.

Seven of them, in fact, though many people overlap:

- visual

- solitary

- social

- logical

- auditory/aural

- tactile/physical

- verbal

Here's a free online quiz you can take (I scored 15% auditory, 50% visual and 35% tactile, for example).

When I tweeted about this, some disputed the idea of specific learning styles; as Heather pointed out, though, the more ways you can present information to someone, the more engaged they will be and more likely they are to retain knowledge, regardless of whether they're actually an auditory or logical learner, etc.

Don't expect to grow a skateboard into a sedan.

This concept was expounded upon in Larry Garfield's talk on "Software Management Lessons from the 1960s":

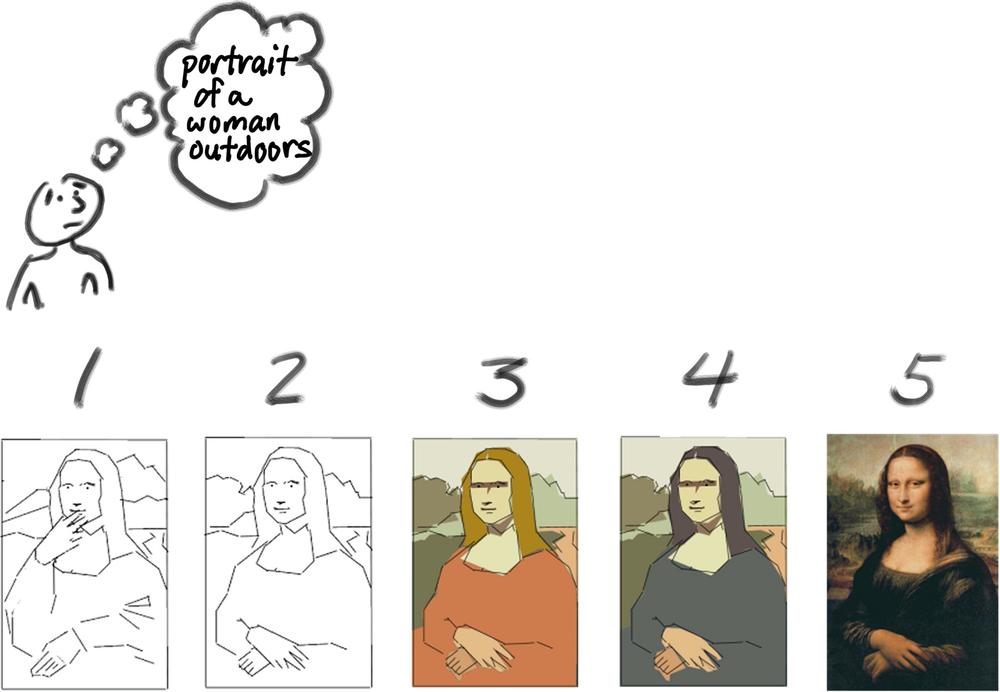

My friend Emily, a PHP conference regular, directed me to this image (from one of her talks), which also illustrates this point:

This is how we try to think of things at Ten Forward, where we use "sprints" when planning our development process. The idea is to hone in on one or two features each sprint and get those to minimum viable product before moving on to the next thing. I hadn't much thought about the benefits of this process until Larry's talk.

For example, in the first diagram, a wheel by itself is rather unusable, and starting with a skateboard involves lots of wasted time building parts you're ultimately going to reject or replace.

Instead, get something built that's basic but works, and fits the bigger picture template of what you know will be following. Additional sprints should build upon, not overthrow, what's already been created.

Include users in the decisions

💯 (via @eryno) #mwphp17 #tech #development pic.twitter.com/YB9I98KMoY

— Hilary Stohs-Krause (@hilarysk) March 18, 2017

This tenet of programming was echoed throughout the conference, including in Eryn O'Neill's thoughtful, impactful keynote presentation. She cited the story behind the concept of "inadvertent algorithmic cruelty" as just one example of harmful programming that could easily have been fixed, if only there were a faster, easier way for the user (Eric Meyer) to communicate with the developer (Facebook).

Make it easy for users to contact you. We can’t anticipate every human’s needs, but we can make it easy for them to tell us. @eryno #mwphp17

— David Lim (@dabidosan) March 18, 2017

Similarly, Emily focused on the importance of user input in her talk on working with legacy code. Her team rewrote a university scholarship application that had well-documented issues, and had caused headaches and heartbreak for students in the past.

Key to updating legacy app: INCLUDE USERS IN THE DECISIONS. Be open about existing errors, work to rebuild trust. @elstamey #mwphp17

— Hilary Stohs-Krause (@hilarysk) March 17, 2017

This can be hard, especially if the error-prone code is yours, but it's crucial to writing good software.

Even if you created the original app, when rewriting, you have to create a safe space for users to give honest feedback. -@elstamey #mwphp17

— Hilary Stohs-Krause (@hilarysk) March 17, 2017